As the ocean swirled around my ankles and receded back with a whoosh, I had what can only be called a revelation.

It was exactly a year ago, which feels more like ten. My father was dying across the country, and with no way to travel safely without endangering my family, I had resigned myself to letting him go from a distance. Collectively, we were all managing lives skewed by quarantine, stockpiling masks and toilet paper as society seemed to unravel around us. Images of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks and so many more boiled in our minds and on our screens.

Our family joined the peaceful protests organized by local activists last June as much as to align with our cultural convictions as we did to experience some limited human contact. I felt a reassuring sense of community as I chanted and carried signs proudly next to my children, nodding in solidarity with our neighbors. We were humbled to see local pastor Ricky Temple moved to tears by the fists of every age and color held in the air as we kneeled in Johnson Square.

But when it came to joining in the profound ritual of Juneteenth on Tybee Island, I wasn't sure I belonged.

After all, it wasn’t until I moved to the South that I even learned about Juneteenth, the anniversary commemorating the day the news of the Emancipation Proclamation was delivered to the slaves of Galveston, TX on June 19, 1865, more than two years after it was penned by President Lincoln and almost three damn months after the Confederacy surrendered.

Locals will note that freedom came earlier to Savannah, when General Sherman showed up in December 1864 after the Union Army’s ruinous March to the Sea and was so taken with the city’s charms that instead of burning it to to a crisp he presented it in all its antebellum glory to President Lincoln as a Christmas gift. Marring this lovely legend—as well as Sherman’s status as some kind of pristine hero—is the Union Army’s hideous act a few weeks before at nearby Ebenezer Creek that caused the drowning of thousands of newly freed refugees.

Juneteenth, also known as Jubilee, is recognized by 48 states (South Dakota’s reticence should surprise no one, but hey, Hawaii, get your act together) though state workers get a paid holiday in only eight, including Texas, Virginia and New Jersey. Celebrations vary among communities, from festive barbecues to readings featuring notable Black writers to the annual “Dia de Los Negros” in Coahuila, Mexico, where descendants of Black Seminoles who escaped across the border honor their heritage.

On Tybee Island, Gullah Geechee powerhouse Sistah Patt Gunn has led a Juneteenth procession at North Beach for the last five years, the diverse crowd swelling into the hundreds in 2020. Surely the horrific recent events had inspired many to attend for a chance to gather safely and perhaps soothe the fear and anger in the cool water. With the air punctuated by drums and the sonorous voice of Sirdeepy Frazier and other members of Gunn’s performance troupe The Saltwata Players, the sky itself seemed to listen, the clouds crystalline in the sun’s rays.

My people don’t really do baptisms (we can talk about mikvehs another time), but as I followed Sistah Patt’s whirling white skirts into the sea, I understood my place in the world in a way that I had not before. I realized that though I may not be directly related to the African people captured, tortured into servitude and finally freed, my presence on this beach, at this time, mattered. That participating in the joy of freedom with these descendants and feeling the rhythms of their rattles vibrate in my bones connected us in a visceral way, the spiritual chains that bind us apart from history and from one another shaking loose, even if just a little.

As human beings, our ancestral histories can be specific, but never separate. There is evidence that traumatic experiences imprint our DNA, affecting the health and potential success of future generations, a scientific inquiry that has been applied to both African American and Jewish people. Perhaps the trauma of pogroms and concentration camps embedded in my genes gives me a certain perspective, but 2020 for me was the year the barriers between the Black American narrative and mainstream history were forever dissolved in my mind and heart.

Perhaps that happened for some of you, too. And now that you’ve felt it, you see the connections everywhere. That Sistah Patt chooses this spot each year for Juneteeth is no accident; it is also the site of a more recent sacred act, the 1963 Civil Rights Wade-Ins when dozens of brave Black teenagers led by legendary local NAACP chairman W.W. Law—including future Savannah mayor Edna Jackson—protested what was then-Savannah Beach’s segregation statutes.

Though its Black residents remain a much smaller minority than in Savannah, Tybee has progressed plenty since, and much more as of last year. New markers commemorating the wade-ins now stand at the entrance to North Beach, thanks to the passage of a racial equity ordinance first brought to vote by City Councilmember Nancy DeVetter that includes instating Juneteeth as a paid city holiday and installing interpretive panels at the former slave quarantine site at Lazaretto Creek, where ships dropped their sick and starving prisoners to be made presentable for their new masters.

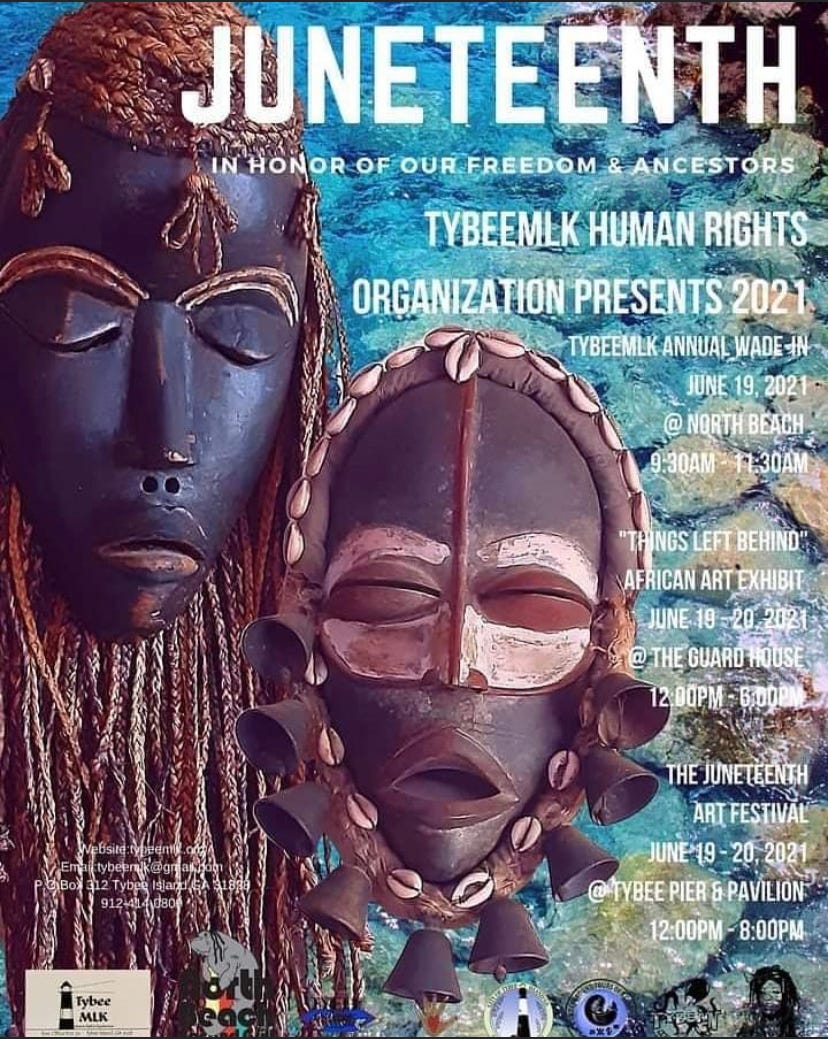

The effort towards equitable representation on the island centers around the Tybee MLK Human Rights Organization, founded by longtime Tybean Julia Pearce (read Jane Fishman’s fabulous profile here.) Aided by 81-year-old ally Pat Leiby, artisan/designer Rafaela Johnson, and dynamic activist Gwendolyn “GG” Glover, this intrepid group has planned an entire weekend of island-wide events for Juneteenth 2021 in addition to the wade-in on Saturday, June 19 at 9:30am.

“This is a homecoming for all people, not just Black people,” affirmed Julia last week when we all met for a round of Arnold Palmers at North Beach Grill. “We mean for every resident and visitor to Tybee to know that this is part of their history, too.”

Folks can park their cars at North Beach on Saturday and Sunday to take a free trolley to see art at the Pier as well as the yellow guard house at Jaycee Park, where Rafaela has curated “Things Left Behind,” a vibrant multimedia exhibit incorporating artifacts of West African livelihood and ritual. The installation serves as a timeline that illuminates the ancestors’ resilience as they suffered the horrific Middle Passage and more than a century of slavery, as well their vital contributions to the origins of America itself. (We all know by now that the colonists would have straight-up starved if not for the agricultural knowledge and actual seeds tucked into heads that came from Africa, right?)

“They brought with them a culture, a wisdom, a spirituality that informed their lives and carried them to freedom,” Rafaela told me. “We can connect with that.”

We talked about the concept of sankofa, both a West African word and Adinkra symbol that means “go back and fetch it,” a command to continually bring forward the ancestral past in order to heal—and be healed by—the present. When applied through art, sankofa’s power is not simply symbolic but offers a portal to acknowledge the sacrifice of those who came before and transmute it through a collective lens as a guide to move forward.

“The takeaway is that for all we went through and what we contributed, there has always been collaboration with one another—not just Black people, but everyone,” reminds Rafaela. “This is about the power of unity, and that power is what it takes to keep us all free.”

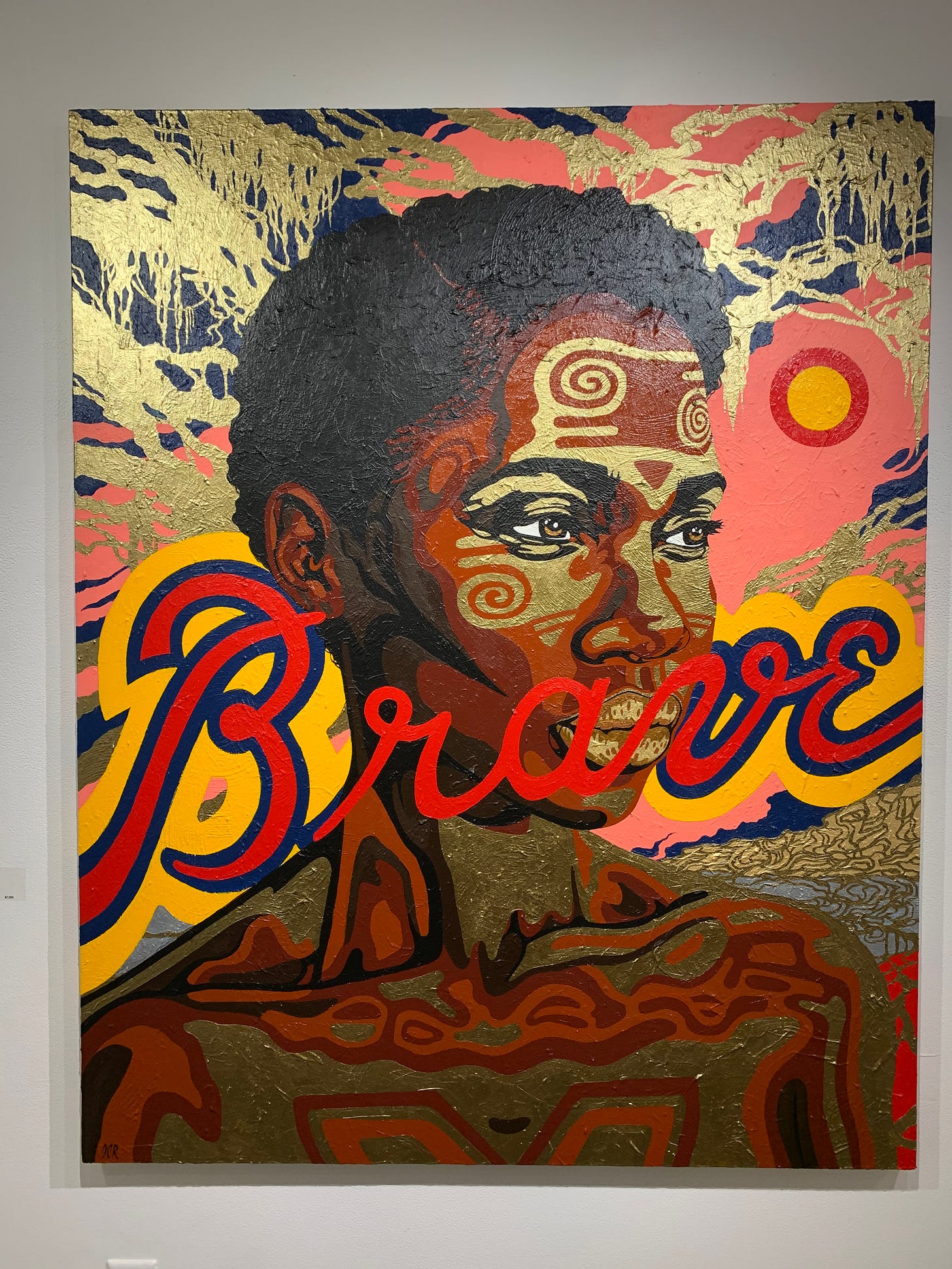

Sankofa figures prominently into another Juneteenth exhibit in Savannah this month. “A Return To…” is on the walls at Sulfur Studios until June 20, featuring a consciousness-raising array of media by contemporary BIPOC artists from Julio Cotto-Rivera’s tribal imagery and Jerome Meadows’ haunting collages to video installations by Antonia Larkin and Tatiana Cabral-Smith that probe the unique viewpoints of women of color.

“When artists explore ancestral ties and ideas of reconnection of the past in the present time, it has an effect on the future,” muses community lightning rod Alexis Javier, who curated the Sulfur show. “In that meeting point, we can ask, ‘where do we go from here?’ and actually get somewhere.”

A year after the summer that brought so much to the surface, it’s still radically unclear where we’re going to end up. While police shootings continue and the cultural divide widens, there’s been a type of muted progress: The world is finally learning the truth about the 1921 Tulsa Massacre, or rather, that it even happened at all. Sistah Patt has filed to rename Calhoun Square to Jubilee Square, logical argument No. 1 being that the racist it was named for wasn’t even from Georgia, anyway.

Also, after months of delays, the City of Savannah appears to be gathering its druthers to relocate busts of a couple of Confederate generals from Forsyth Park after they’ve been subject to tens of thousands of dollars worth of vandalism. Them’s some real nice Confederate monuments you got there, be a real shame if anything happened to them...

Speaking of relocation, the Black college beach party known as Orange Crush has moved to Jacksonville from Tybee Island after 30 years of clutched pearls and snarled traffic restrictions. I’m not sure if it counts as progress, but I’m glad these kids will at last get to party somewhere where their money and youthful exuberance will be appreciated.

“I think the city of Tybee missed an opportunity to show unity, and I think they’ll be back,” opined Julia about the perpetual polemics around Orange Crush, which was excluded from the final version of Tybee’s racial justice ordinance.

Wherever we’re going, the road is long and often leads backwards. Last week an Effingham teacher resigned after school officials reprimanded him for mentioning the Black Lives Matter movement to his majority-Black classroom, and we’ve got Gov. “I Didn’t Know KOVID Was Kontagious” Kemp decrying critical race theory in schools, though most intelligent people seem to understand the need to present a more representative version of American history rather than the nationalistic circle jerk contained in most current textbooks.

Then there’s all the systemic racism to dismantle, not always obvious or even nefarious but nevertheless embedded into so many aspects of American society, from housing to education to property taxes to healthcare. (FYI, people of color continue to bear the brunt of COVID-related impacts.)

“It’s exhausting,” Julia sighed as our conversation wound down, the ice in our tea glasses melted.

At that very moment, a young white woman walked by on her way to the beach, her t-shirt bearing the slogan, “You Don’t Have To Be Black to Support Black People.”

“Look at that! Can I take your picture?” Julia asked the girl and her grandmother, her face beaming.

This invigorated the whole table, a sign that while the work may be heavy, it continues to flow towards peace, and perhaps the ancestors are watching over us all.

Whether you think it’s your holiday or not, I wish you and yours a joyful, jubilant Juneteenth—all of us deserve freedom and the chance to celebrate it. If you want to learn more and you’re around Savannah this weekend, the Jepson is hosting a free admission June 12 & 13 in its observance, opening with a libation ceremony Saturday at noon with local treasures Vaughnette Goode-Walker and Jamal Touré.

I’m sorry to say I won’t be wading in the water with y’all this year. I’ll be in Arizona that weekend with my family, finally able to honor my dear dad a year after he passed, another ancestor to watch over us. But I’ll be there in spirit, feeling the waves of joy around me as I lift my hands to the sky.

After all, when we feel the connection to the whole of humanity and its history, it’s not something that we can ever wash away.

Yours in unity ~ JLL

Beautifully done! History, emotion, fairness and unity--Who's not on board with that?