Long before I was born, my maternal grandmother painted.

At first, her canvases reflected realistic subjects, flower still lifes and portraits of her favorite movie stars. At some point, such literal lines dissolved, the colors becoming richer, the layers marking wild movement and chaotic emotions untethered to any particular form. As a child, I found them terrifying, feeling as if they might eat me as I would pass by the three or four hanging in the hallways of our home.

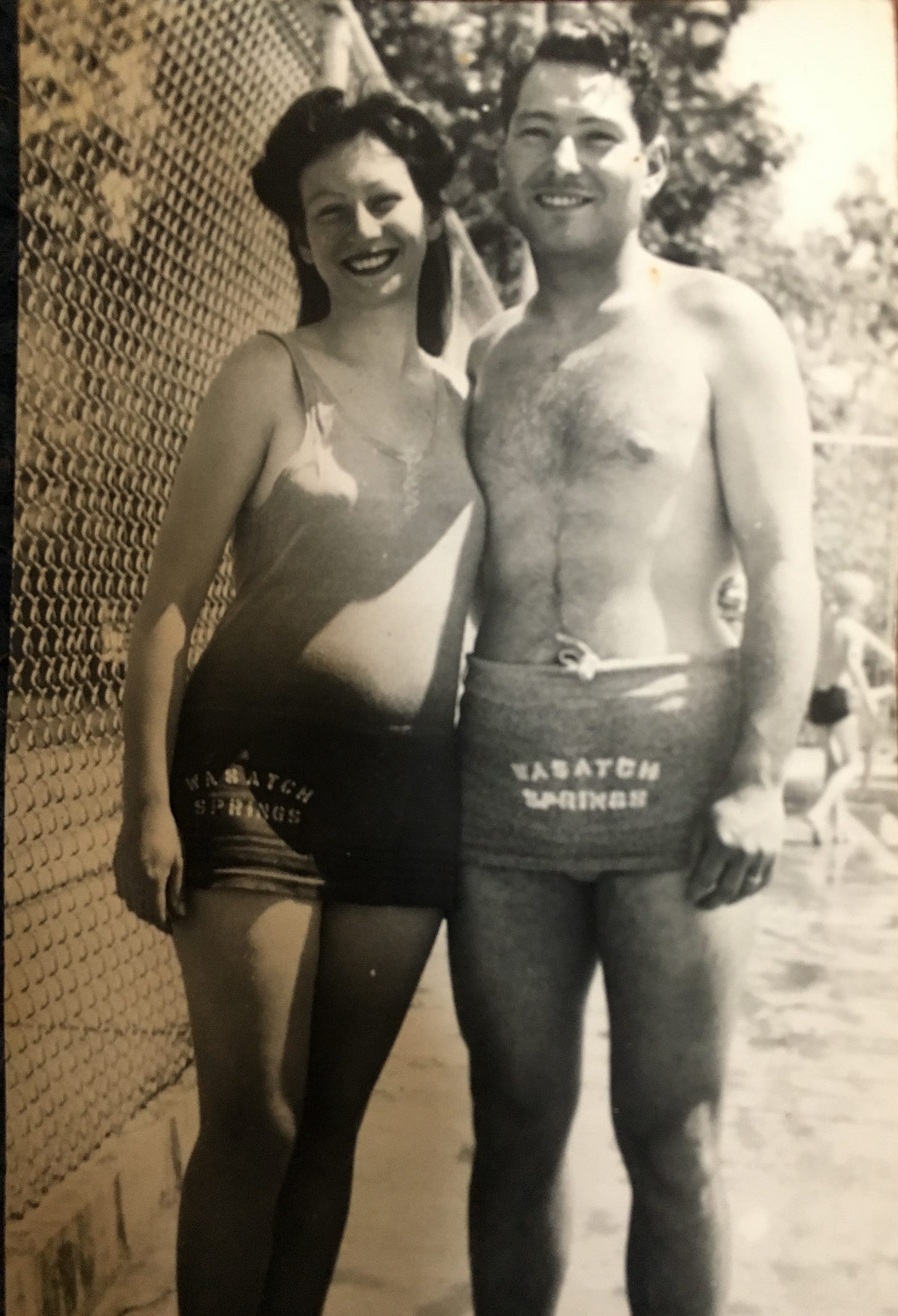

Regina Dines Blumenthal was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1933, the same year Hitler took power, setting the stage for his extermination of Europe’s Jews and other undesirables. Her father, Nathan, heeded the gut feeling that things were about to get really terrible and made the harrowing passage with his wife and small daughter to America, leaving behind a sprawling network of kin too entrenched in Warsaw’s cultural and social stations to believe anything could happen to them. Their names are among the Six Million murdered at Auschwitz and other death camps.

In New York, young Reggie married my musician grandfather, George, and moved to the Miami hamlet of Coconut Grove, where she studied art with renowned painter Tony Scornavaca until rheumatoid arthritis disfigured her hands in her 40s. By the time I came toddling around, she could only tell stories, some of which live on in my own mother’s book, Paper Children. My Bubbie Reggie passed away in 2007, scattering among our small family a few dozen canvases that I learned to appreciate and became fascinated by as I experienced my own emotional depths.

One of these has hung in our living room for the last 20 years, a lively abstract full of blood red and black, cryptic moods and memories churning in the layers. It is this painting that our daughter chose as her inspiration for her design for the Savannah Arts Academy’s Junk 2 Funk fashion show, a beloved tradition showcasing how public schools can get it right. Overseen by inimitable art teacher Meghan Scoggins, this year’s theme was “Off the Canvas,” provoking breathtaking interpretations of Picasso, Monet, and other art icons that would have had my bubbie cackling with glee to be included amongst.

Our daughter crafted her dramatic dress entirely from scratch, sewing and modge-podgeing strips of color for weeks while we binge-watched Search Party. When her model, the lovely Rhayne Williams, sauntered down the runway with Bubbe Reggie’s painting projected on the screen behind her, my heart ricocheted like a swallow set loose in my ribcage.

Here was a collaboration 70? 80? years in the making, threaded across time and space—and yes, as a matter of biological fact, uteruses. Did you know females are born with all of their eggs already in place, meaning we all existed inside our mothers from their own infancies, and they inside theirs, and so on all the way back to the first mothers?

It’s a mind-blowing notion made material as I watched my bubbe’s great-granddaughter join her own creation on the stage. I have always understood intellectually that if my great-grandfather hadn’t caught the scent of danger in the convivial atmosphere of post-WWI Europe, I would not be here. But seeing the painting and the dress and my daughter’s beautiful face with its Asiatic cheekbones that hearken back to when (my mother says) Mongolians invaded the Russian shtetls, I shuddered. I suddenly perceived clearly the loop of generations that have come before and through me, the self-same patterns of life in motion, a fractal writ large.

We are all here because our ancestors survived. Be they smart or strong or lucky, they managed to stick around long enough to pair up and make another human in a world without treated water or vaccines or anesthesia or disposable diapers, where starvation and brutality and atrocity lay around every corner. While Ancestry.com may give up a few names from recent centuries, those we will never know still influence us every day.

That is not mystical or symbolic hyperbole; again, it’s straight up biological fact. Our ancestors literally live on in our cells, in our very DNA, expressing themselves not only in the wonky way our eyebrows grow or a risk for cancer but in our behavior, our mental health, and our capacity for resilience.

My mother, the historian and writer Marcia Fine, first introduced me to the study of epigenetics as she was writing Paper Children, citing research conducted on the children of Holocaust survivors who had an altered stress gene related to PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders. The trauma their parents endured in the concentration camps had changed their genetic phenotype, affecting their future offspring by passing on predilections for neuroses or courage.

"The implications are that what happens to our parents, or perhaps even to our grandparents or previous generations, may help shape who we are on a fundamental molecular level," writes lead scientist Dr. Rachel Yehuda, who has probably made her parents very proud. “That contributes to our behaviors, beliefs, strengths, and vulnerabilities.”

Many more epigenetic studies on intergenerational trauma have been conducted among other ethnic groups, including African Americans, paving a path to the recognition and treatment of inherited trauma disorders. While we cannot change the past or save previous generations from pain, perhaps the acknowledgement that we still carry it in ourselves can help release it.

My grandmother escaped the Holocaust, but I imagine that she bore deep scars within. Her father, while prescient, was prone to violent abuse, perhaps influenced by the poverty and injury of generations before him. I surely hope all the therapy I did in my 20s to work through the anxious and self-destructive tendencies that had plagued me since childhood helped reduce whatever mishegoss I passed on to my kids, whether it was on a genetic level or just not being as reactive as I might’ve been otherwise.

All I know is that seeing Bubbe Reggie’s powerful painting onstage interpreted by her great granddaughter so many years later gave me the overwhelming sense that somehow, something had been healed.

Because—FACT—life is a fractal, this same idea of reconciling ancestral trauma as we heal ourselves came around again the very next day. Seems patterns are always repeating if you’re looking.

On March 25, Lazaretto Day on Tybee Island commemorated the enslaved Africans who set foot on land for the first time since their abduction many months before at the oyster-encrusted beach at the mouth of Lazaretto Creek.

“‘Lazaretto’ means ‘quarantine,’ and this is where they brought people to be sorted before they were sold into slavery in Savannah,” explained Julia Pearce, the indefatigable leader of Tybee MLK Human Rights Organization who champions the call to “honor the past to better the future” by telling the missing stories of the island’s history.

Gathered under the oak trees were many familiar faces, including Sistah Patt Gunn, still working to realize Susie King Taylor Square, and storyteller supreme Amir Toure, who gave voice to the hundreds of thousands trafficked as part of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, “those who made it and those who did not.”

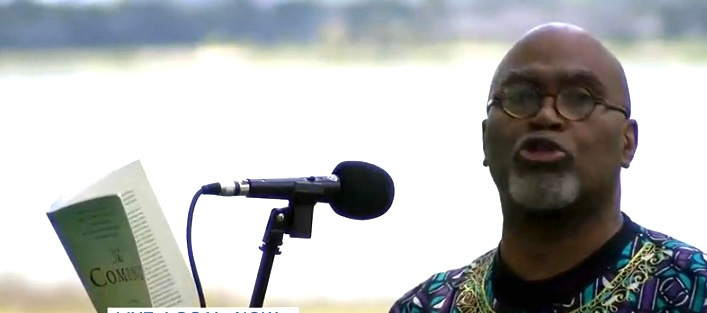

New to me and most compelling was Dr. Daniel Black, professor of African American Studies at Clark Atlanta University, who shook the trees with a reading from his book, The Coming, a riveting narrative of a slave ship that begins with the chilling hindsight of those who ignored the coming disaster. “They could not say there weren’t signs,” he intoned with sonorous sadness. “They could only say they did not heed them.”

The ancestors that arrived on this beach are not my ancestors, yet my heart aches for them. Their terror and loss, the unspeakable horrors they endured, so imprinted on their DNA and passed down through their descendants, compounded by centuries of racism, violence, and erasure. The sprawling network of their kin—our own neighbors likely among them—have such a heavy load to bear. It feels only right to stand with them as they name their people, mourn and tell their stories.

And then a young person comes around and sets loose the burden. Poet activist Patrice Jackson came forward to kneel on the same sacred ground, extolling the wisdom these survivors brought, how to grow food, and make medicine by aligning with “intelligence of nature.”

“To access the parts of self tucked away in ancestral knowledge is a simple, powerful magic,” she noted gently before leading a ritual of placing hands on the ground to feel the connection.

“Touch the earth when you need assistance.”

It was a prescient reminder that if we look back far enough, all our ancestors come from the same place. We owe our existence to those tenacious, clever people. We owe it to ourselves to do what we can to heal their trauma.

For guidance, we don’t have to call our ancestors—they have been with us all along. We only have to turn in and listen.

We are each other’s people ~ JLL

This was a tough one but a beautiful one! Thank goodness ur grandfather was cautious. So sad that many who were so close to them (& u) did not make it. Horrifying. Ur children are so lucky to know so much about those that came bf them...especially HOW MUCH THEY FAVOR THEM IN APPEARANCE! Holy cow, those genes do run strong. So cool that ur mom is in her tummy in that pic. I loved search party too! Hate to admit I didn't love the final season, but anyway... Thanks for the interesting story & great J2F job, Liberty! So cool & special.

Jessica, you make me get the feels every time I read your words, but,honey, this week is just awesome! What a master writer you are!