As the daughter of a second wave feminist, the fact that I did not grow up playing with dolls should surprise no one.

In the nascent momentum to unravel gender stereotypes for children, my toybox did not contain any of those stiff-limbed figures in frilly dresses or porcelain pretties with painted-on pouts. (You’re right; I didn’t have an E-Z Bake Oven, either.) I didn’t mind much, since I found Raggedy Ann’s triangle nose terrifying, and the ones that peed in tiny diapers grossed me out. Also, until I was eight, I legit thought Madame Alexander was the heroine of a Russian novel I was too young to read.

Don’t worry, I kept myself plenty busy with my feminist-sanctioned Bionic Woman action figure and Stretch Armstrong, along with a veritable village of Smurf figurines. But I understood early on that cutesy baby dollies weren’t for a girl like me, and as a matter of fact weren’t just for girls anyway, as sung by Alan Alda and Marlo Thomas on the Free to Be You & Me soundtrack (which is still the most brilliant kids’ musical of all time and makes Frozen seem like imbecilic mewling.)

I did have my curiosities, though, and would steal over to the neighbors’ house to ogle her Barbie dream house, bringing my Smurfs to ride around in the pink convertible kept in the plastic garage. But the Barbies themselves, with their long blonde manes and little tiny noses always made me uncomfortable for what I would learn to call “unattainable beauty standards,” and also probably because my neighbor’s older sister would make them hump each other in the backseat.

Later I would come to appreciate this vanilla introduction to teen sexuality and also find out that Barbie was actually invented by a smart Jewish lady with a fabulous fashion sense, but back then all I knew was most dolls represented a childhood that didn’t look or feel like me, no matter what Whoopi Goldberg thinks.

And in spite of the 1970s’ burgeoning revolution and revelations on gender and culture, I didn’t have the wherewithal to even realize how it affected others. If I thought blond-blue-eyed dolls were exclusionary, I’d never even considered how the few African American dolls I’d seen, which looked identical to the smiling lady in a head scarf on the syrup bottle, were stereotypes, too.

While Leo Moss of Macon, Georgia is credited as America’s first mass producer of Black dollmaker in the 1890s, followed successful entrepreneur Henry Boyd who founded the National Negro Doll Company in 1911, mainstream toys remained white by default until well after WWII. In her memoir, newspaper editor and journalist Wanda Scott recalls how her mother, who was a retail buyer for military outposts with one of the biggest toy budgets in the country in the 1970s, singularly convinced behemoth toy manufacturers Hasbro and Mattel to bring Black dolls to market in at the behest of the families of African American servicemen.

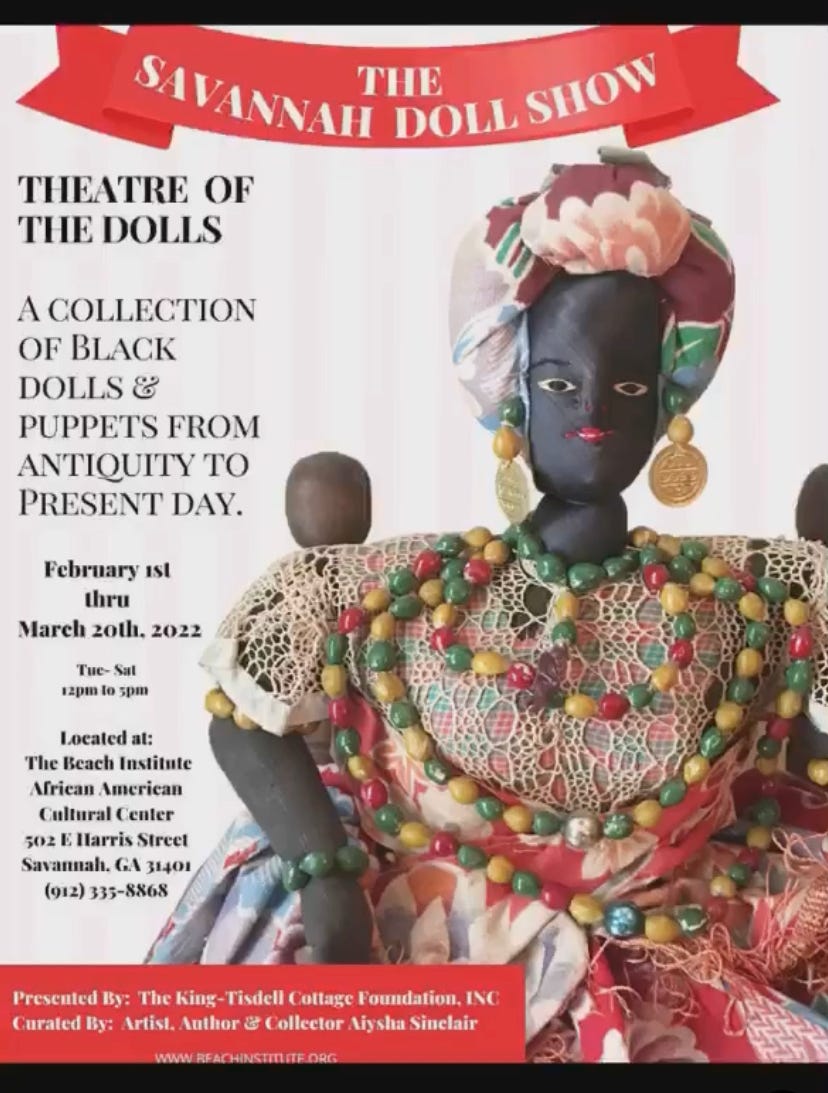

Of course, there have always been handmade dolls, pieced together from scraps and found materials by loving elders. Some of those stereotypical “mammy” dolls date back to before the Civil War and have found their way into the collection of author and artist Aiysha Sinclair, who has curated Theatre of the Dolls, an extraordinary exhibit at the Beach Institute through March 20.

“Because of the nature of how history was or was not recorded, there is no way of knowing who created them, they can only be dated by the fabric,” said Aiyisha as she arranged the delicate figures around the Institute’s gorgeous gallery space last week.

“While we may find it offensive now to see Black dolls dressed as washerwomen and such, it gives us a glimpse of what was. They become our little storytellers.”

Ranging from those ancient, anonymously-crafted fabric forms to limited edition Madame Alexanders to a 1960s bride adorned in seed pearls and lace, the exhibit also tells the story of the African Diaspora in so many countries of origin: A hand-painted dancer with gold-coin earrings from her father’s homeplace in Trinidad, a trio of raffia statues from Guyana, a long-faced marionette carved in Mali that will star in the puppet shows performed on Saturday afternoons throughout the exhibition.

“Some of these were made to comfort a child, and have now passed through generations,” explained Aiysha. “These dolls are a way to connect to culture.”

The show includes more than 70 pieces, including some wizened little moppets she made herself with dried apples and sticks, a tradition that dates back thousands of years to indigenous civilizations around the world. The author of the Brown Sugar Fairies series has been collecting Black dolls and puppets since she was a little girl, scouring estate sales and thrift shops, though she admits to enjoying her share of modern novelties.

“I definitely had a Cabbage Patch doll in the 80s, her name was Elaine,” she laughed. “The official Hobby City Cabbage Patch Hospital was near our home in L.A. and I would take her in to listen to her heartbeat.”

Perusing the historic provenance, gorgeous tiny clothing, and adorable faces of Aiysha’s dolls, I kind of wished I could pretend to hear their heartbeats, or maybe at least sit down with them for a tea party. I also realized that while not playing with dolls may have saved me from internalizing certain stereotypes as a kid, I also might have missed out on learning more about people who didn’t look like me.

Research shows that playing with dolls aids in the development of empathy and social skills, which probably still wouldn’t have convinced my mother to buy me a Barbie. In these times, however, introducing other cultures and ethnicities to the tea party is a revolutionary act—though you know some testy mom from the carpool line will accuse that American Girl doll of teaching Critical Race Theory. *rolls eyes*

Though I don’t have any regrets about being raised by parents who were sensitive to the way culture shapes from our earliest days, I’m glad I gave my own children free reign over their plaything options. The few Barbies that found their way into our home never stood a chance against the Beanie Babies and plastic dinosaurs when it came to who my kids identified with, but they did receive horrific haircuts from a stuffed raccoon. In one of my proudest early parenting moments, our 5 year-old son once chose a dark-skinned babydoll from a pile of prospective toys and named it Scott. I like to think Alan Alda would have approved.

By the way, I did receive not just one but TWO Barbies of my very own for my 50th birthday, gifts from my lovely friend Elizabeth Shelton, who thought I’d been denied long enough. She said she’d break out her old dream house from her attic for a tea party if I bring the wine.

She also promised we can take Barbie’s pink convertible for a spin, but let me tell ya honey, the Smurfs call shotgun.

And you and me are free to be you and me ~ JLL

Marvelous, darling! You said it all. I love the commentary and your observations. I was firm in my beliefs that my children wouldn't be brainwashed into gender roles. My parents were eccentric bohemians who didn't question it; however, your other grandparents were appalled that I requested a lawn mower (much to my chagrin because it made a most annoying growling sound) instead of a baby carriage. Gems that they were, they bought both!

What a wonderful showcase for the exhibit! I wish I could see it. No Barbies! I admit it! I was in a Women's Studies program at ASU at the time. We had lectures on the "Dangers of Barbie's" to little girls' identity! But, you did have a giant doll that was the size of you at two. She wore one of your dresses which was covered in large pink flowers. I know because I saved her until the last move because I knew you'd give me "rolled eyes" if I ever showed it to you. You were a very cute little girl. BTW, the pregnant yellow possum with 8 attached babies made it until November of 2021when a helper fell in love with her. Well-preserved in an old zippered mattress covering bag!