On the lovely blue bungalow tucked away in a grove of moss-cloaked old oaks, the fuschia front door stands out like a flirtatious sentry.

The entryway of the home of bestselling author and literary icon Rosemary Daniell embodies the coquettish charm of its legendary denizen, who greets me wearing a tank top, wraparound skirt, and flip flops all in the same rosy hue.

“Come in, come in, I’m so glad you’re here,” she murmurs in her soft Atlantan drawl, ushering me into the living room packed with several sofas in various floral prints to accommodate the writing groups she has hosted here for decades. Accented with throw pillows and richly-patterned artwork, the space feels like a cross between a lavish cocoon and the inside of the bottle in I Dream of Jeannie.

It is unapologetically ultra-feminine, much like Rosemary herself, who embraced the color pink long before it was reclaimed as an emblem of female strength and positivity à la Barbie.

“Pink has always been associated with women, and that’s who has come to my groups for all these years,” she muses, referring to the tight-knit legion of sisterly scribes known as the Zona Rosa.

Her husband (her fourth, who’s been around almost four decades), Tim “Zane” Ward, acquiesced to the female energy long ago. He sticks his head out for a hello before disappearing in a back bedroom to leave us ladies with the brindle-streaked cats, Flower and Frida (after Kahlo, every creative woman’s kindred spirit.)

A proper-born Southern belle who married far too young and could have easily faded into a life of repressed desperation, Rosemary instead forged her own definition of womanhood. In the early 1960s, the mother of three small children found a stray thread of the coming counterculture in a continuing education poetry class at Emory University, unveiling a portal where new definitions and personal truths could be shared.

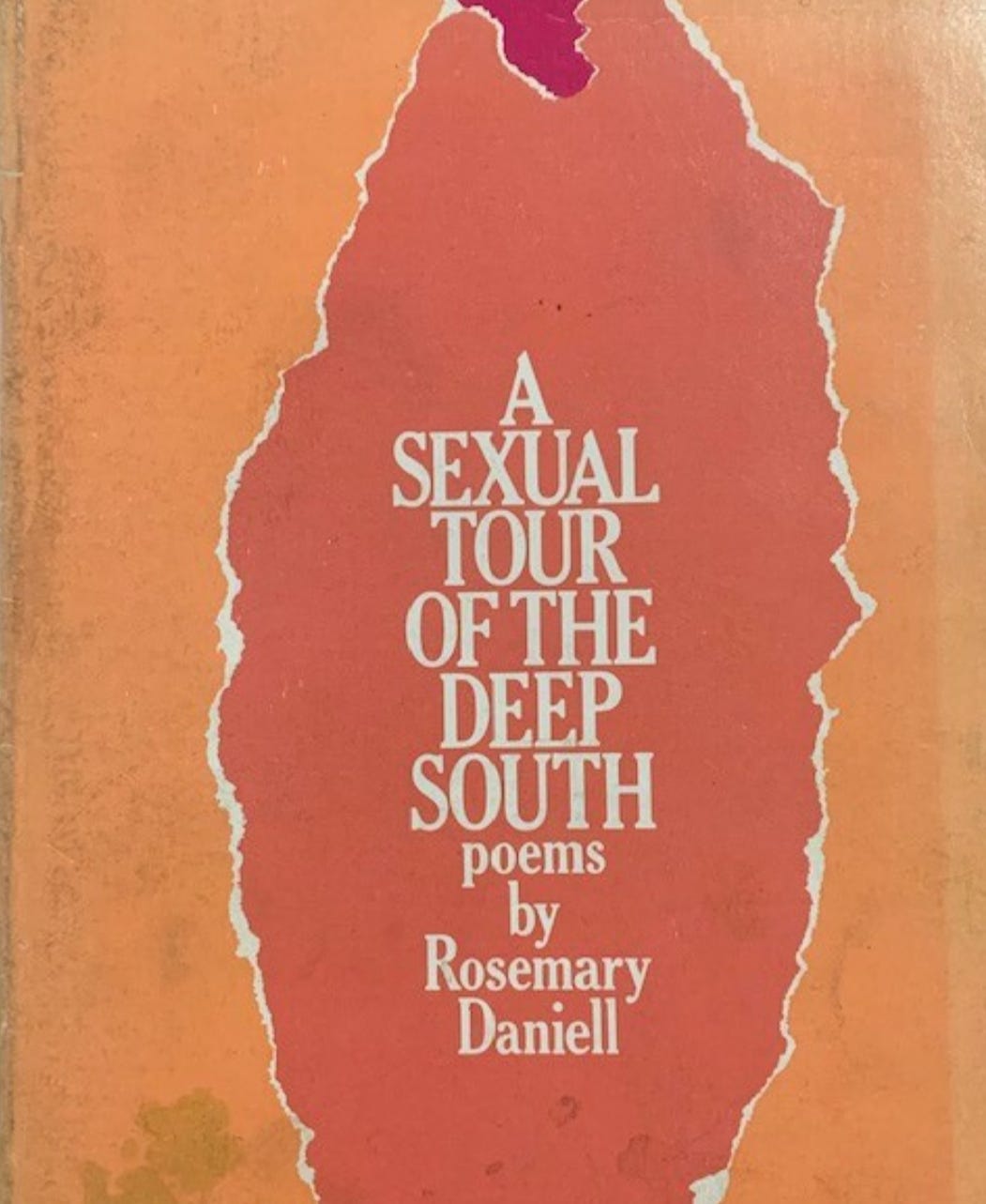

Her first collection of poetry, A Sexual Tour of the Deep South, chronicled those first years of sexual and self liberation and was met with national acclaim, causing much pearl clutching amongst the church ladies and their ilk. Rolling Stone lauded it as one of the most important feminist works of the times, though Rosemary’s love of lipstick and unabashed adoration of macho men rankled some sourpusses in the mainstream women’s movement.

“Guilt is one of those useless emotions I refuse to indulge” is one of her oft-quoted aphorisms, still meme-worthy after two more waves of feminism.

While her chapbooks along with her titillating, often tragic memoirs found an eager audience, Rosemary also forged journalistic pursuits, publishing countless contributions to newspapers and magazines from the New York Times Book Review to Southern Living to our own Savannah Morning News.

But the writing that Rosemary is perhaps most renowned for is not hers. The aforementioned Zona Rosa groups have produced millions of pages of prose from its members, many of whom have gone on to professional literary careers themselves. Most of them, however, first come for instruction and often permission to finally tell their own stories.

After moving to Savannah in the late 70s on an NEA fellowship, Rosemary led writing workshops in the public school and women’s prisons before holding her first women’s writing group in that first ramshackle downtown apartment.

“I thought I’d stop after six months,” she recalls, noting that her rent was $195 a month. “The next thing I knew there was a waiting list.”

In these workshops and on retreats, many acolytes found their voices for the first time, secrets revealed and provacative phrases coaxed out in camaraderie. Beset by her own tragedies—her mother died by suicide, her father of cancer, her three children fatally plagued by illness and addiction—Rosemary has been a willing midwife to help others navigate their trauma by writing it out and sharing.

The small gatherings proliferated, taking Rosemary all over the state and then the globe to nurture safe, soft spaces to bring inner lives to the page. She kept her own notes to translate into popular writing guides, The Woman Who Spilled Words All Over Herself and The Secrets of the Zona Rosa, encouraging anyone who wants to write to sit down and get busy.

“She has always been so supportive of other women,” says another self-actualized Southern lady, Miriam Center, a Zona Rosan since the early 80s and author of the memoir Scarlett O’Hara Can Go to Hell, first drafted on a ream of onion skin paper in a living room workshop. (Miriam—who turns 98 this Friday—also tells me that she and Rosemary used to go out carousing in the Savannah bars together back then, which must’ve been some seriously adorable trouble.)

Most Zona Rosans are women, with a few notable exceptions: When a young John Berendt began hanging around Savannah looking for story ideas for Vanity Fair, Rosemary invited him into her rose-petaled sanctuary and introduced him to a flamboyant antique dealer named Jim Williams, paving the way for the Book that changed the city forever. (For the record, Rosemary was the first to document Williams’ trial in her 1986 essay, “The Scandal that Shook Savannah.”)

There’s also our own homegrown New York Times bestselling mensch Bruce Feiler, who counts Rosemary as an essential mentor in his career and calls her a “national treasure.”

Bruce will surely have more accolades to bestow this Sunday, August 11 at the Tybee Post Theater when he moderates a celebration of Rosemary’s work and legacy, Wine, Women, & Words. Zona Rosa stars from near and far will honor the impact this tiny, soft-spoken redhead has had on their writing and being, the revelry bound to spill over into the audience. Tickets are available and include drinks, sweets, and other goodies.

Afterwards, the guest of honor will probably return to the little blue bungalow with the hot pink door to work. At 88, she no longer commutes all over the Southeast but still spends hours a week poring over Zona Rosa drafts, offering suggestions on punctuation and gently pushing women to dig deeper for their truest stories.

“I still have piles of manuscripts to read before our next Zoom meeting,” she frets, wondering aloud how to find time for her own work, including publishing the recently completed memoir, My Beautiful Tigers: Forty Years as the Mother of an Opioid Addicted Daughter and a Schizophrenic Son.

Sitting in her kitchen with Flower the Kitty on my lap (Frida is the elusive one, go figure), I feel lucky to have this generous guru all to myself. We chat about the mechanics of writing, and also men (so cute, yet so annoying), but when she asks if I’ve ever considered committing to a full-length memoir, I hem and haw.

It’s not that I need permission to tell my own stories, I explain, pointing out that I cast myself plenty into these weekly missives. I’m just not sure plumbing further into my own messes would do anyone any good at this point.

“I bet they would … for you,” she says with a smile, handing me a copy of one of her writing guides, brimming with accounts of women whose words opened their lives wider than they’d ever imagined.

I ask her if she’ll sign it, which she does.

In pink ink, of course.

Thank you for updating us on Rosemary! Both of you are Savannah icons with lots of stories to still tell. It's lovely to see you together!

Women expressing themselves means we all learn something. Keep sharing!