I don’t know when adolescent angst hits in turtle years, but Addy the Famous Loggerhead sure was acting like a teenager raring to get out of the house.

Days before her third birthday and her release back to the ocean, I had the honor of visiting this renowned reptile at her temporary digs at Tybee Island’s Burton 4-H Center, where she was twirling toys around her tank with the joyful abandon of a goth kid in a mosh pit.

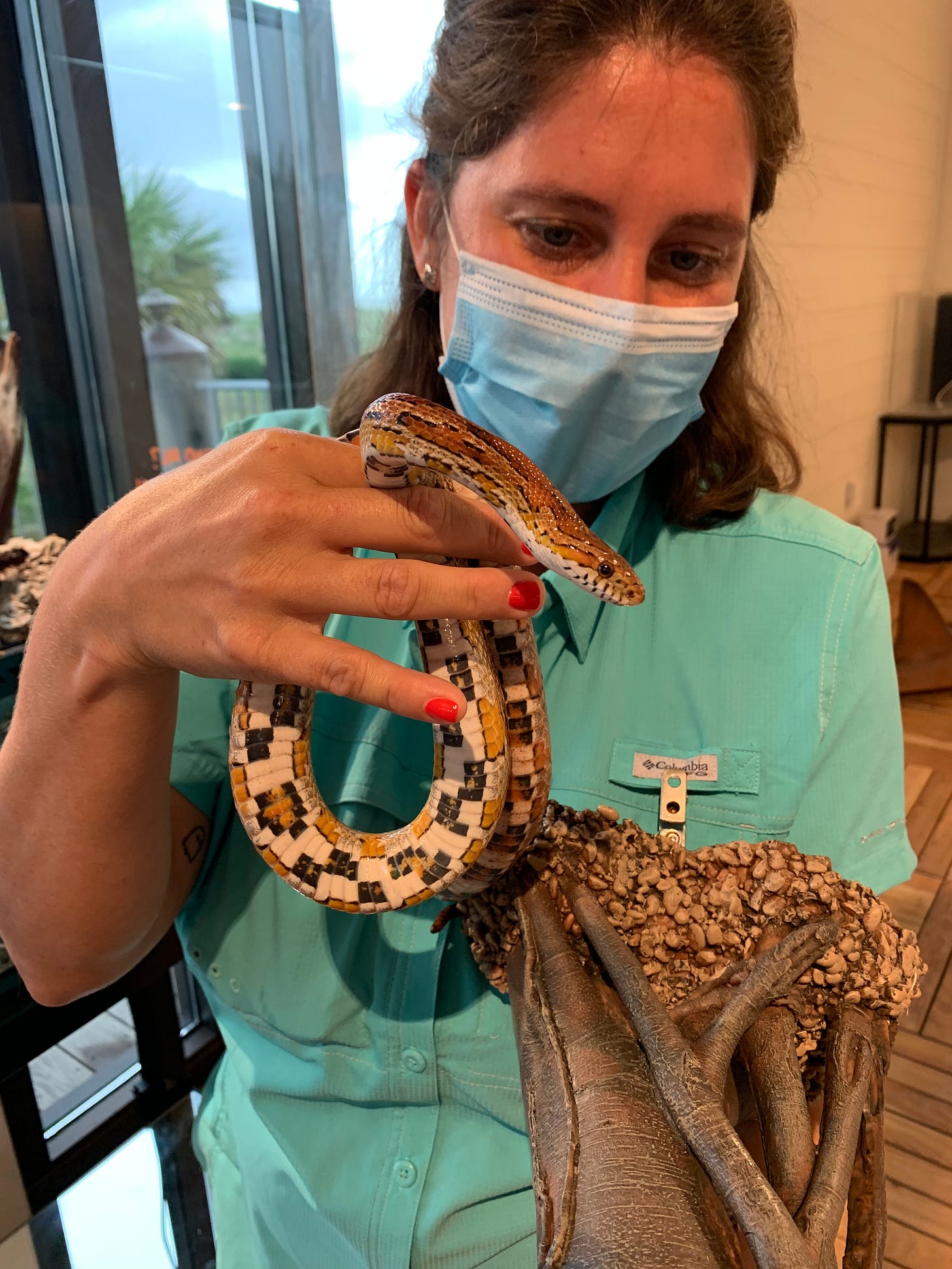

“Oh, are you showing off?” scolded marine biologist Chantal Audran as Addy booped her beak against the glass in greeting.

As the executive director of the Tybee Island Marine Science Center, Chantal has been the closest thing Addy has had to a mom after she and five siblings were rescued from a trashcan by an intrepid housekeeper at the island’s Admiral’s Inn in the summer of 2018. The world went wild for the story of their capture by some well-meaning tourists from Kentucky, who were apparently not aware that kidnapping endangered species is a punishable offense or that it’s never a good idea to bring anything back to your hotel that you find drunk on the beach at night.

After her potato chip-sized sistren were returned to the sea, Addy quickly grew from Child Celebrity Trash Turtle to one of the center’s most popular attractions and important educational tools. It is presumed that all the hatchlings were female as they came from the warmer top of the nest; as climate change fries the globe, an estimated 98 percent of loggerhead babies will be girls. While girl power is important, it doesn’t bode well for the species.

Now at a healthy 56 lbs from a wholesome diet that has included live crabs, cannonball jellyfish and other food sources she’ll find out in the wild, the time had come for Addy to leave the tank. Chantal and her staff had been preparing all year, and Dr. Terry Norton of Jekyll Island’s Georgia Sea Turtle Center gave the all-clear. Outfitted with new flipper piercings to help researchers recognize her in the future, all Addy needed was some black eyeliner and Doc Martens to make her seem like any other young woman ready to take on the unknown.

I might be projecting, what with all the stomping around my house and breaking of curfews by our high school senior.

Chantal swears that of the six loggerheads she’s raised to maturity and released back to the wild, Addy has the most personality. But the sea turtle expert holds no illusions that the bonding only goes one way.

“Look, I’m a scientist. She’s going to get out there and her primitive brain will take over. She doesn’t have a frontal cortex, she’s not going to remember me,” said Chantal, tossing Addy a shrimpsicle.

“But that’s never stopped me from singing to her,” she added with a grin.

Nursery rhymes aside, Addy will never know what she’s missing in the magnificent new TIMSC facility overlooking the island’s north beach, though her superstar status surely helped raise the profile of the Center’s fundraising efforts. The grand 10,800 square-foot building opened this summer for tours and camps but wasn’t quite ready to receive a denizen of Addy’s size, hence her extended playdate at the 4-H Center.

A glorious upgrade from the city-owned spot near the pier where it shared a sidewalk with public bathrooms for 30 years, the ultra-clean design by local architectural virtuoso Christian Sottile features two floors of animal exhibits including Ike, the year-old tyke who replaces Addy as the center’s resident “marine debris ambassador.” The rest of the space includes several sunny classrooms, an amphitheater with ocean views, a gift shop full of plush ocean-themed stuffed animals, and a 15-foot touch tank where Chantal and her brilliant staff teach visitors about our delicate coastal ecology and why plastic bags and straws are the worst.

Founded by a group of teachers 30 years ago, the marine science center has always been about more than looking at cute animals. Longtime board member Jeanne Hutton pointed out that the stunning new edifice is built with a cantilevered roof to capture rainwater and extra strong pylons to withstand hurricanes, an education in itself as it sits among Tybee’s historic batteries ready to do battle with rising sea levels, freshwater depletion, and plastic pollution.

The $7.4M project has been funded three-fourths of the way thanks to its capital campaign co-chairs, financial wizard and deep sea diver Doug Duch and legendary local naturalist Cathy Sakas, who has had a paddle in practically every oceanic conservation effort in Georgia, from co-founding Gray’s Reef Marine Sanctuary Foundation to protecting the Okefenokee Swamp to chairing the Tybee Island Beach Task Force.

Our family has eagerly pledged our support, as my husband has been hankering for a real science museum ever since the one of his youth on Paulsen Street closed over 25 years ago. (Shout out if you remember walking through the ventricles of the giant heart.)

The contribution is also sentimental: Our own kids have been poking their fingers in the center’s touch tank since they were practically hatchlings themselves and keeping vigil around the yellow-taped loggerhead nests in the summers. On one special night, we watched a nest boil with baby turtles and tiptoed behind them as they crawled to the sea under a full moon.

Chantal was their counselor at Sea Camp, showing them the wild spirals that birth tiny whelks, and she coached our daughter’s Savannah United soccer team for a couple of seasons. She whistled in disbelief when I told her that the little girl who liked to tickle horseshoe crabs and steal the ball was entering her senior year of high school this week (as the captain of the soccer team, woot!) and that soon she’ll be off to college, leaving behind a messy bedroom full of empty eyeliner tubes and plushies from the TIMSC gift shop.

Poetic perfection would have been for my baby to hug her coach and bid farewell to Addy on the eve of her emancipation, but life’s most important lesson is that it’s not perfect.

Instead I dragged along her older brother, who supposedly left the nest years ago but has been hunched over the kitchen table all summer studying for his medical school entrance exams with monastic discipline, mowing through boxes of granola bars and craisins. The chance to meet Addy was the only success I’ve had at enticing him away from his flashcards in three months, and the drive out to Tybee was one of few precious moments with him before he goes back to Athens next week for his last year of college, and then, who knows?

I squeezed back tears and concentrated on conflating my maternal concerns with Addy’s imminent independence.

Will she find enough to eat? (Chantal assures that she’s an excellent little hunter.)

Will she make friends out there? (Probably not; sea turtles are solitary except for brief mating encounters.)

Please God, don’t let her eat a plastic bag or suck a straw up her nose. And keep the sharks far, far away from her (and everybody else, too; a speedy recovery to you, Hot Sushi!)

And while we’re praying here, please convince the data heads at the Corps of Engineers to call off the turtle-chopping SHEP dredgers during nesting season. (Actually, we can do that ourselves by adding our names to the 100 Miles petition—this is an imminent issue that affects our endangered right whales as well.)

Let Addy grow to her full 400 lbs, and if the fates see fit, help her land back on Tybee in 20 to 30 years to dig her own nest and drop her pearly eggs in the sand, the spot cordoned off perhaps by gentle souls who learned to love the great mystery of the world in the beautiful building down the beach. And if there is such a thing as poetic perfection, let it be my kids tending her nest, perhaps with their own hatchlings in tow, turning over horseshoe crabs in wonder.

As much as I tried not to anthropomorphize Addy, I was definitely sobbing two days later when Chantal and her staff led her procession towards the ocean.

Amid cheers of “Swim, Addy, Swim!” she scurried like she’d just snatched the car keys, hemmed by the scientists who saved her life, surrounded by hundreds of volunteers and fans. Standing ankle deep in the water, I couldn’t help but think of and send thanks to the village of family, friends, teachers, coaches, and counselors who have provided guidance and boundaries to my children as they realize their own destinies.

The saltwater mixed with tears as I shared a hug with environmental reporter and community treasure Mary Landers, who was the first to break Addy’s story at the Savannah Morning News and has recently joined the investigative journalism team at The Current. Look for Mary’s stories holding the Corps, the Port, and other industry accountable for the Georgia coast and all in its inhabitants.

She sputtered as the first crest lapped over her shell, then Admiral the Sea Turtle pushed herself off into the waves and disappeared, the flash of one flipper raised in what we’ll take as a grateful farewell. (You can see the first swim here, though I cannot find footage of that miraculous last goodbye.)

Thankfully, she didn’t do anything embarrassing, like refusing to take direction or cussing in front of guests.

“She could have been a lot naughtier,” sniffed Chantal with a smile. “She did great. She has that primitive brain, she’s going to be fine.”

With any luck, and prayers if you believe in them, the prehistoric instincts buried in that brain will bring her back to this same beach someday.

And while she may lack a frontal cortex, Addy definitely has a strong, beating heart.

May she be guided by it, its strings invisible and wholly unscientific, into the great unknown.

Just keep swimming, babies ~ JLL

Support local science—Become a member of the Tybee Island Marine Science Center!

Like this column? Share it! Love it? Subscribe!

Thank you for sharing this story about Addy and the new center.

Stop making me cry! Loved this one! ADDYYYYY!👋 She's like bye bish... oh & thx I'm sure altho teens usually forget that part. Petition signed.