When you’re renovating an old house, sometimes a long-forgotten treasure will turn up.

There’s the English family who uncovered a cache of gold coins in the floorboards, and that poor guy who found his Christmas gift 45 years too late.

Of course, major renos can also bring out gnarly discoveries like bat nests or human remains, which is why we’re leaving our 85 year-old pink-tiled bathroom intact forever.

But barring a genuine samurai sword or a life-size Monopoly board, the best thing you can dig up during a remodel is a great story. And couldn’t we all use more of those?

Author Jason Friedman found a gem of tale when he and his husband, heralded LGBTQ+ filmmaker Jeffrey Friedman, bought a condo in a regal 1875 Greek Revival mansion on the corner of Liberty and Barnard over a decade ago. Most home construction jobs seem interminable, but in this case tracking down all the literary twists took a lot longer to complete than the drywall.

Eager to land an East Coast pied-à-terre, these denizens of San Francisco’s Noe Valley had purchased the place sight unseen. A few surprises awaited when they arrived to make it their own, such as the vintage brass chandelier in the dining room and the realization that the stately townhome wasn’t actually constructed of smooth white stone but rather covered in scored stucco, as was architecturally fashionable in the day.

Also unanticipated was a link to original homeowner Solomon Cohen. Though a Californian for most of his adult life, Jason is a Savannah native (he worked at the Pirate’s House in high school; no more solid street cred than that around here) and grew up in the city’s storied Jewish community over which Solomon and his kin wielded unmatched influence in the late 19th-century. (If your eyes have ever wandered while sitting in the pews at Congregation Mickve Israel, you might’ve noticed the stained glass window dedicated to Solomon’s brother, Octavus.)

Research at the Georgia Historical Society and other sources turned up a wealth of references to Cohen, including a mention as a “rich lawyer” in General William Tecumseh Sherman’s official memoirs—as well as documentation that the local alderman and Confederate state senator owned over a dozen enslaved workers, some of whom he rented out to neighbors. This uncomfortable and unforgivable history loomed over a lifetime of dedicated public service and the founding of several enduring Savannah institutions, including GHS itself.

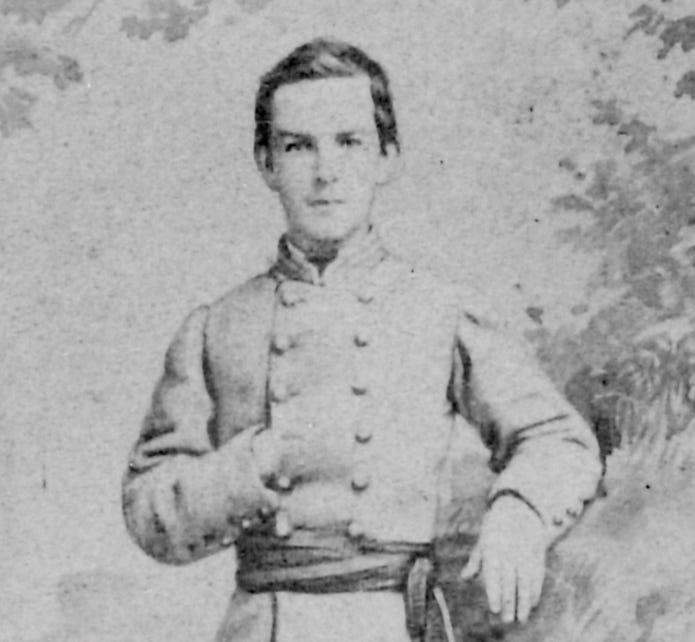

But it was Solomon’s son, Gratz, who truly piqued Jason’s curiosity. Described as both a “handsome martyr for the Confederacy” and a passionate, poetic young man with health issues and a “sensitive disposition,” the short life of Gratz Cohen offered up a dusty window to a time when attitudes around masculinity and social equality weren’t necessarily as simple as they seemed.

Uncovering Gratz’s unmistakable queerness as well as his deep loyalty to family and faith struck a personal chord in Jason. Though conflicting and sometimes disturbing, the historical hints proved irresistible to the 21st century’s reluctant Southern son, who at 18 had fled the “small stifling place where everyone knew me better than I knew myself, or thought they did.”

“Growing up gay and Jewish in Savannah, that was definitely part of my feeling of connection to him,” muses the writer, who spent countless hours poring over a few fragile pages of Gratz’s diary, inked in a “maddening, faded scrawl.”

“I also began to think of ‘queer’ in the larger sense, in that he didn’t have the right kind of masculinity for the South at that moment, which I found heartbreaking and mysterious.”

He spent the next several years chasing clues and traveling to all sorts of sites connected to the Cohen family, including the state park at Hofwyl-Broadfield Plantation and the University of Virginia, where Gratz became the first Jewish student in 1862.

He followed wisps in local ledgers to find out more about an enslaved man named Louis, who Gratz refers to as his beloved “valet,” and credits tour guide and consummate sage Vaugnette Goode-Walker for opening his eyes to Savannah’s integral role in the global slave trade.

“Vaughnette made that whole world come alive for me,” recalls Jason, who had learned little of the history of Bay Lane in school.

“We were kept in the dark by design, and it still remains a secret history to an extent.”

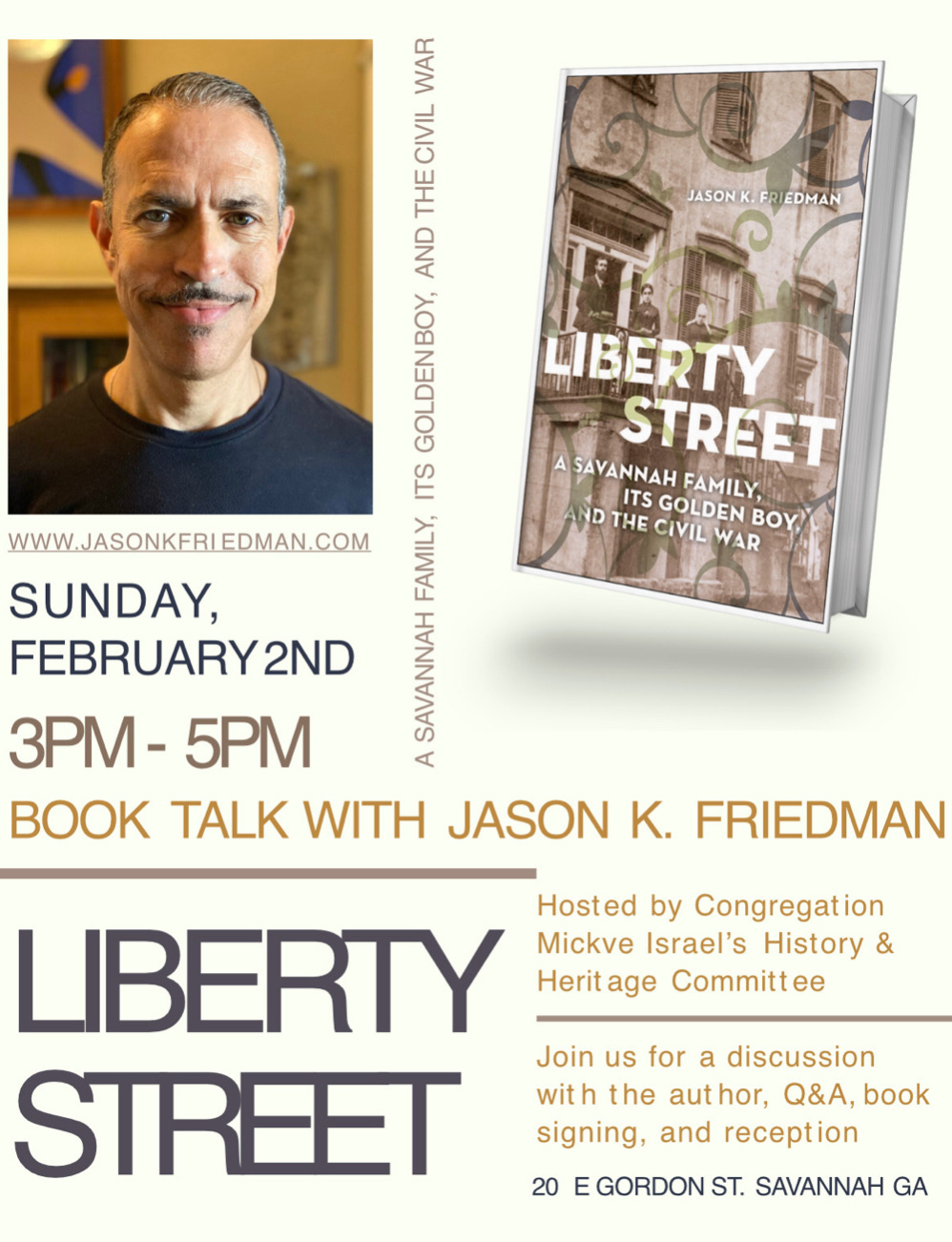

As the new paint dried and the gents filled their flat with art and furniture, Jason gathered the story bit by bit, adding his own salient reflections. He published Liberty Street: A Savannah Family, Its Golden Boy, and the Civil War last year with the University of South Carolina Press.

The book reads as both an enthralling historical mystery and a gimlet-eyed examination of how a prominent Jewish family thrived at the height of the Confederacy. It’s been singled out as a Good Morning America Buzz Pick and drawn comparison to The Hare with the Amber Eyes, Edmund de Waal’s bestselling epic about a Jewish family in pre-war Europe.

One afternoon last fall I happened to be loitering at The Book Lady when Jason was in town for a few days, and we exchanged the polite pleasantries of fellow creatives hustling their wares.

I took a signed copy of Liberty Street home, thinking that it would probably meld into the teetering stack of future reads on my nightstand. I mean, what more about the Civil War did I really need to know?

Instead, after thumbing through the introduction, I found myself quickly invested in the unexpectedly sweet, brave Gratz as well as Jason’s thorough and engaging process of peeling back the layers of history. The pacing keeps up with the rabbit warren of research tracks, culminating in the wrenching circumstances of the young soldier’s death. The only spoiler I’ll give is that flat feet didn’t keep this complex young man from defending the world he believed in, as unjust as it was.

Jason has been making rounds on both coasts at Jewish community centers and synagogues to promote the book, including Mickve Israel this Sunday, Feb. 2 at 3pm. He’ll be in conversation with another renowned Savannah author (and newly-installed synagogue president, mazel tov!) Jonathan Rabb, a meeting of minds sure to evoke as many questions as answers. (I’m quite bummed to miss it due to a previous engagement.)

However—to paraphrase my favorite poster at Pinkie Master’s—you don’t have to be Jewish to find fascination in Liberty Street. Anyone interested in Savannah and American history will appreciate the deeper look into the contradictions and complexity of a time easy to dismiss for its inexcusable inequities, and perhaps there are lessons to apply to what many of us consider our country’s current backwards slide.

As with most home renovations and fact-based stories, there’s always more to add. After he’d already turned in the manuscript to the printer, Jason acquired more astonishing relics: Gratz’s ancient pistol and another earlier diary that reveals this privileged son had his own questions about the enslaved humans who served his family and city.

“He writes more about Louis, acknowledging that his ancestors were stolen,” reports Jason, who plans to add some of these excerpts to the book’s second printing. He says he can only wonder what other thoughts remained unwritten.

“Would he have continued to become more enlightened had he lived a full life? I’d like to think so.”

Most of us like to think of history as immutable, though previously hidden pieces tend to keep showing up that change the way we perceive it. No one’s life—not even the shortest ones—can be reduced to their obituary, and assumptions can be dashed with every new discovery.

Speaking of which, the Friedmans weren’t entirely disappointed when they found out the stone of their historic townhouse was just a facade. Underneath the once-preferred stucco was the original Savannah grey brick, handmade by enslaved people in the 1700s at Hermitage Plantation and now a coveted asset in the housing market.

Just goes to show: Whether we’re talking about old houses or the glories of the past, the most valuable treasure we can uncover is the truth.

Fight the power, read local ~ JLL

I loved this column as an amateur historian and a renovator of several Savannah homes. I also refuse to apologize for something that occurred in the distant past. Was it horrific? Yes!!! Did it tear up the fabric of a society that had no choice in the matter? Yes!!! Do we have an obligation to call this sort of thing out today as well as much of what is occurring right NOW? Damn right, YES!!!! And I believe in pink bathrooms, preferably with black trim. It's historically accurate. We had one in our 1920's New York home. Happy New Year.

Whoa - thank you! I love this and will make every effort to go on Sunday. And we did tear out that pink tile in the bathroom - no regrets. ;-)